User:Robbie/rmcc narrative bio 2pp: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

<p>Through all my schooling, I was poor at assigned learning, but ardent in independent study, in the classical sense — striving after, concentrating on, favoring, applying oneself, giving attention to, being eager, zealous, taking pains, diligent, devoted to. With the bookstore as my curriculum, I studied my way through Princeton, sparked by avid reading in the work of the Spanish thinker, José Ortega y Gasset. At Columbia, I made the verb, to study, the means and goal of my career. With free rein from my dissertation sponsors, Lawrence A. Cremin and Jacques Barzun, I went all out on an intellectual biography of Ortega, defended in the spring of ‘68 in the midst of campus turmoil. It became a large, well-received first book, [https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1971_man_circumstances_all.pdf Man and His Circumstances: Ortega as Educator], published in 1971. </p> | <p>Through all my schooling, I was poor at assigned learning, but ardent in independent study, in the classical sense — striving after, concentrating on, favoring, applying oneself, giving attention to, being eager, zealous, taking pains, diligent, devoted to. With the bookstore as my curriculum, I studied my way through Princeton, sparked by avid reading in the work of the Spanish thinker, José Ortega y Gasset. At Columbia, I made the verb, to study, the means and goal of my career. With free rein from my dissertation sponsors, Lawrence A. Cremin and Jacques Barzun, I went all out on an intellectual biography of Ortega, defended in the spring of ‘68 in the midst of campus turmoil. It became a large, well-received first book, [https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1971_man_circumstances_all.pdf Man and His Circumstances: Ortega as Educator], published in 1971. </p> | ||

<p>Simultaneous with the book’s publication, I received tenure, and within the domain of Ortega’s influence, the work brought recognition from writers like Jacques Ellul and Salvador de Madariaga. | <p>Simultaneous with the book’s publication, I received tenure, and within the domain of Ortega’s influence, the work brought recognition from writers like Jacques Ellul and Salvador de Madariaga. A short-lived high-point, I found difficult to move beyond. I began to drift, uncertain what should come next, seeing life as a public intellectual an improbable dream. I reflected on political and educational thinking from Rousseau forward and explored how modes of communication and material life affected personal and collective self-formation, but found it difficult to establish public or professional interest in my work. In a school of education, many professors and students perceived my thinking to be tangential, too distant from the actualities of public schooling.</p> | ||

<p>Should I | <p>Should I have moved elsewhere? Perhaps, but with tenure among colleagues I liked in a major university in a great city I loved, I stayed put, committed to turning my youthful commitment to study into a full theory and practice of education. In life, a persistent question can become a quest: <i>Can each person find within their actual circumstances resources requisite for pursuing comprehensive, life-long, voluntary study? Can each, grasp actual opportunity to study as fully as they will find worthy what their vital concerns compelled them to devote themselves to?</i></p> | ||

<p>Through the 1970s, my essays addressed these and related questions. I properly published a few, among them, “[https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1971_place_for_study.pdf Towards a Place for Study in a World of Instruction]” (1971). Others, like “[https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1973_universal_voluntary_study.pdf Universal Voluntary Study]” (1973), “[https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1976_problems_to_predicaments_hew.pdf From Problems to Predicaments]” (1976), and “[https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1977_imperative_of_judgment.pdf The Imperative of Judgment]” (1977), I circulated as not quite finished manuscripts. My experience broadened through a year of solitary immersion in the milieu surrounding Frankfurt’s Goethe-Universität (1973-74), and through a wholly different whirlwind as a special assistant to the U.S. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in Washington (1975-76).</p> | <p>Through the 1970s, my essays addressed these and related questions. I properly published a few, among them, “[https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1971_place_for_study.pdf Towards a Place for Study in a World of Instruction]” (1971). Others, like “[https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1973_universal_voluntary_study.pdf Universal Voluntary Study]” (1973), “[https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1976_problems_to_predicaments_hew.pdf From Problems to Predicaments]” (1976), and “[https://rmcc4.com/pdf/1977_imperative_of_judgment.pdf The Imperative of Judgment]” (1977), I circulated as not quite finished manuscripts. My experience broadened through a year of solitary immersion in the milieu surrounding Frankfurt’s Goethe-Universität (1973-74), and through a wholly different whirlwind as a special assistant to the U.S. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in Washington (1975-76).</p> | ||

Revision as of 15:13, 5 January 2025

Robbie McClintock

After a long academic career, I live in Princeton to study how education and technology interact and to nurture intelligence, judgment, and care by improving digital tools for personal use.

Born in 1939, I grew up preferring sports to academics, doing just well enough on the scholastic escalator until I formed a sense of purpose as a Princeton undergraduate. Then, I wrote a good senior thesis, aced comprehensives, and in 1961, received my BA, unexpectedly with high honors.

Columbia followed, where I studied history and thrived after a bad start as a somewhat picaresque academic — tilting with the doctoral mill, emerging well- certified yet undisciplined. In those days, the old-boy network plus a great job market created magical opportunities — a phone call recruited me, 3 years beyond the BA, as a tenure-track assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins University. Two years later, a similar call initiated my return to Columbia, where I joined the Teachers College faculty in 1967. There I stayed, rising through the ranks to become the the John L. and Sue Ann Weinberg Professor in the Historical and Philosophical Foundations of Education in 2002.

Through all my schooling, I was poor at assigned learning, but ardent in independent study, in the classical sense — striving after, concentrating on, favoring, applying oneself, giving attention to, being eager, zealous, taking pains, diligent, devoted to. With the bookstore as my curriculum, I studied my way through Princeton, sparked by avid reading in the work of the Spanish thinker, José Ortega y Gasset. At Columbia, I made the verb, to study, the means and goal of my career. With free rein from my dissertation sponsors, Lawrence A. Cremin and Jacques Barzun, I went all out on an intellectual biography of Ortega, defended in the spring of ‘68 in the midst of campus turmoil. It became a large, well-received first book, Man and His Circumstances: Ortega as Educator, published in 1971.

Simultaneous with the book’s publication, I received tenure, and within the domain of Ortega’s influence, the work brought recognition from writers like Jacques Ellul and Salvador de Madariaga. A short-lived high-point, I found difficult to move beyond. I began to drift, uncertain what should come next, seeing life as a public intellectual an improbable dream. I reflected on political and educational thinking from Rousseau forward and explored how modes of communication and material life affected personal and collective self-formation, but found it difficult to establish public or professional interest in my work. In a school of education, many professors and students perceived my thinking to be tangential, too distant from the actualities of public schooling.

Should I have moved elsewhere? Perhaps, but with tenure among colleagues I liked in a major university in a great city I loved, I stayed put, committed to turning my youthful commitment to study into a full theory and practice of education. In life, a persistent question can become a quest: Can each person find within their actual circumstances resources requisite for pursuing comprehensive, life-long, voluntary study? Can each, grasp actual opportunity to study as fully as they will find worthy what their vital concerns compelled them to devote themselves to?

Through the 1970s, my essays addressed these and related questions. I properly published a few, among them, “Towards a Place for Study in a World of Instruction” (1971). Others, like “Universal Voluntary Study” (1973), “From Problems to Predicaments” (1976), and “The Imperative of Judgment” (1977), I circulated as not quite finished manuscripts. My experience broadened through a year of solitary immersion in the milieu surrounding Frankfurt’s Goethe-Universität (1973-74), and through a wholly different whirlwind as a special assistant to the U.S. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in Washington (1975-76).

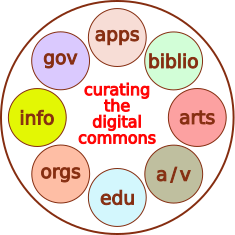

As the decade ended, I felt fully committed to my quest to make universal, voluntary study actually feasible for all, but I had formed deep doubts that I could do much about it as a scholar and critic, doubts I expressed in “The Dynamics of Decline: Why Education Can No Longer Be Liberal” (1979). I had become primed to change the course of my quest significantly, and I became a historical materialist of sorts, bent on making digital technologies serve everyone as an affordable, effective place to study.

In 1983, I became chair of Communication, Computing, and Technology in Education, a department at TC. In that move, I organized the Institute for Learning Technologies (ILT) in 1984, directing it until 2002. I secured substantial funding through numerous proposals, among them — The Cumulative Curriculum Proposal (1990-91), which spawned two large projects — The Dalton Technology Plan (1991–1996) and The Eiffel Project (1996–2001). We won over $20 million in grant competitions and supplemented that with equivalent matching effort from diverse organizations. We implemented high visibility projects to prototype advanced resources enabling study by means of the emerging Internet in New York City schools, public and private, and in Columbia University.

Proposals I wrote said little about how cognitive research could enhance instruction and lot about how historical innovation could improve conditions for study. I addressed how cultural and educational transformations emerging with digital technologies are uncertain and unpredictable in many proposals, reports, talks, and essays. Among them, two extended essays, Power and Pedagogy (1992) and The Educators Manifesto (1999), and the pedagogical rationale for a huge public-private collaboration attempted on the eve of the dot-com crash, Smart Cities — New York: Electronic Education for the New Millennium (2000) still deserve attention.

Over the past 20 years, I’ve concentrated on scholarship and technical initiatives “for their own sake.” In Homeless in the House of Intellect (2005), I explored how the academic study of education might have a place within the ongoing historical transformation of higher education. In Enough: A Pedagogic Speculation (2012), I criticized present-day thinking about education and public life from an imagined perspective, far in the future, when enough — neither too much nor too little — would have supplanted the acquisitive drive for more as the basis for exercising judgment and legitimating authority. Subsequently, I published an extended essay — Formative Justice (2017) — that brings the speculations put forward in Enough more concretely into the contemporary context.

I’m depressed by the anger that has built up in us all. The public sphere has ceased to work, enabling a few persons and organizations to arrogate wealth and power that egregiously exceeds what they can use with wisdom, compassion, or worth. Apparent action by imagined communities displaces our sense of personal agency. The public sphere has become a white noise engulfing us as persons in a din of importuning abstractions about what fictitious entities appear to want, opine, and scheme.

Where to go from here? That's a tough question. One must learn to stand alone, perceiving and acting with Stoic apatheia and Epicurean ataraxia to sustain life as best one can in the actual circumstances within which one lives. For me, that amounts to trtying to construct a place to study where I can use my intelligence, judgment, and care in my actual circumstances to live my life as best I can.

Still so much to do. Here’s to the future!