Texts:1971 On the Liberality of the Liberal Arts

- My user page

- Notes to myself

- Draft book proposal to Princeton University Press

- Forms for page setup

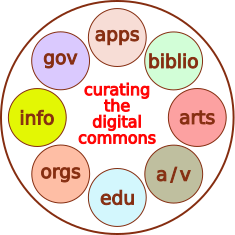

- Links to apps go here

On the Liberality of the Liberal Arts

Teachers College Record, Vol. 72, No. 3, Feb. 1971, pp. 405-416.[1]

Many doubt that students should make academic policy, claiming that the young are ignorant, that their decisions would be unwise. The older tendency to romanticize the student, attributing to him a Rousseauian purity uncorrupted by the wiles of the world, is giving way to sterner strictures: Students are now regarded as fickle, feckless, ignorant of history, mindlessly imbued with dangerous ideologies, devoid of civility. The academic authorities are stiffening. They may yet feel they must bend a little more, but they are getting ready to push back. After all, it is they who are now up against the wall, the financial wall, and further disruptions are likely to run into hard resistance. This clash between the wise pupil and the yet wiser professor is beside my point. The student's claim to pedagogical responsibility should rest not on his wisdom, but on his ignorance. Let us return, not to Rousseau, but to the Stoic teacher, Epictetus: The beginning of philosophy with those who take it up as they should and enter in, as it were, by the gate, is a consciousness of a man's own weakness and impotence with reference to the things of actual consequence in life.

Education, a search for enlightenment, begins not with erudition, but with an awareness of human limitation, ignorance, and imperfection. A student properly begins to learn when he intuits his impotence towards consequential matters; then he can seek fitting remedies. But in school, college, and university, he finds that educators ignore his consciousness of his weaknesses and his desire to overcome his impotence. He discovers instead that his "needs" are defined for him according to weaknesses that others perceive with reference to things of imagined consequence to conventional lives and stereotyped professions. Hence many students dismiss academic policy. No matter how efficient, knowledgeable, and even enlightened it may be, they find it unreasonable, for it ignores what they experience as essential—the living, willing, thinking student.

Roots of Unrest

An example of what disturbs many students is the way that sophisticated academics and politicians explain student unrest. Foregoing the absurd conspiracy theories of political demagogues, they attribute the disturbances to the effect of glaring social ills on impressionable youths. Despairing over Vietnam, misused national resources, and racial injustice, students rebel against what seems the nearest, most vulnerable component of society. Thus in its carefully balanced report to Mr. Nixon, the President's Commission on Campus Unrest explained that "the roots of student activism lie in unresolved conflicts in our national life," among them the great issues of war and race. Doubtless these are excellent points to make to politicians who would rather meddle in the university than attend to the difficult business of ending the war, setting humane priorities, and reconciling racial tensions. But failure by the politicians does not suffice to explain the cantankerous mood of students; the actual roots of unrest may lie in unperceived conflicts within academic life.

To be sure, war, misallocated resources, and black activism have been secondary causes of American student radicalism. But campus unrest is worldwide; it is one of the visible aspects of the cosmopolitan actuality in which all now live. Student radicalism is most virulent in prosperously neutral Japan, with only its small military establishment to absorb the people's resources, where racial divisions hardly exist. Although facing different national issues from within different educational systems, the academic activists in West Germany, France, Italy, Spain, England, Latin America, the United States, and Japan are surprisingly alike. Such facts suggest that American critics are fostering an erroneous diagnosis, for national political improvement alone will not solve campus difficulties.

Outstanding issues, some profound, some passing, will always provide an occasion for the discontented to manifest their disaffection. But now, in diverse countries, beneath the innumerable objects of student protest, a common pedagogical problem will persist, until solved, in turning convenient issues into occasions of academic upheaval. Neither stiffer administrative backbones nor better public policies will solve this worldwide problem. For the academic disorders are not epiphenomena, subsidiary aftereffects of other issues. On the contrary, the source of the malaise is the attitude, endemic among educators, which makes the epiphenomenal explanation seem plausible; the source is the belief that intellectually students are a perfect plastic that receives form only from external influences. The tabula rasa theory still persists.

Observing Academic Affairs

If one steps back, temporarily ignoring the causes of the unrest, one notes an overlooked feature of the situation: numerous people have become intensely concerned about academic matters. The balance between teaching and research, undergraduate mores, admissions policies, faculty and administration selection, university finance, and curricular organization have begun to fascinate even those who formerly cared only about Alma Mater having a winning football season. State politicoes like Ronald Reagan have shown Messrs. Nixon and Agnew that people consider pedagogical policy pertinent not only when their children apply to college, but daily, for they see that the function of state government is increasingly to provide, maintain, and oversee an encompassing educational system. Here is the novel situation: Academic affairs no longer concern the average man only temporarily as his children mature; they are of continuing significance to everyone as primary civic activities.

Proof may be found in student rebellion itself, which is a venerable tradition. Academic upheavals, college closings, and unruly demonstrations can be traced back through the American college to the medieval university and even earlier to the cathedral schools. For instance, the student antics of Abelard—provocative questions that led to disruption and a student secession—are now venerated as the origin of the University of Paris. What is novel is not student demonstrations, nor even the raucous tactics often used, a fact one will learn by investigating, for instance, the history of Princeton's Nassau Hall; what is novel is that so many people now take student demonstrations so seriously, intoning revolution, destruction of the university, or the collapse of reason. Both participants and spectators perceive this seriousness; it gives the current unrest a distinctive character, setting the present demonstrations apart from their predecessors.

In this light the cause that merits study is not the cause of the demonstrations themselves, but the cause of the general interest in the demonstrations. This cause is not the Vietnam war, unseemly spending priorities, or racial injustices; the cause of the concern for academic affairs is not the impact of general political issues upon schools and universities, but the reverse, the influence of schools and universities on public life. By their heightened interest in educational problems, people reveal that they have sensed the degree to which intellectual developments have become powerful influences in public affairs; they seem to suspect that as Harvard goes, so goes the nation. Thus the attention paid to student demonstrations suggests that these are not epiphenomena and that people are beginning to perceive the important influences our campuses exert upon the commonweal.

Mandarin Way of Life

Pundits have already charted how schools and universities gained this public significance. The "scientific-educational estate" holds much power in the new industrial state described by John Kenneth Galbraith. Economic growth is now found by many experts to depend more on intellectual innovation than on financial investment. Planners assume that the relative power of nations varies with the effectiveness of their educational systems. Organized knowledge is applied to all of life from lovemaking to computer programming. Atomic energy and space exploration give two awesome examples of what mobilized intellect can accomplish; and the lesson of these gigantic enterprises is continually reinforced by the mundane yet ingenious artifacts of intellect, by the televisions, telephones, automobiles, airplanes, and computers that affect us daily. People are realizing that production and control of these artifacts depend on the knowledge that is in turn produced and controlled by our educational institutions. Hence often without articulating the thought, people suspect that, as Jacques Barzun has explained in The American University, a Mandarin way of life has developed in which certificates of education mainly determine each person's prospects.

Educators have sensed that they now exercise considerable power in a community whose traditional order of rank has been upset. For centuries those who could mobilize and allocate property held power, for land and money were the scarce components limiting production. Then as industrialism matured, much power passed from the wealthy to those who could organize the new essential, labor; and now power is moving to yet another group, the scientists, intellectuals, and educators who create and allocate knowledge. With power there have come emoluments that are now notorious: reduced teaching loads, generous research grants, appointments to influential offices, respect as an authority on matters of public interest. With power something also comes that is easily ignored; with power educators become implicated in the dilemmas of principle that arise from the inherent ambivalence of power, the way it inevitably seems to convert means to ends.

When a group has power, the decisions it makes are not only substantively important for the whole community, but the way it operates, the way it makes and implements its decisions, set the tone of the common life. Power enables a group not only to perform its restricted function, but in doing that, to determine what modes of practice—the liberal or the paternal, the good or the mediocre, the open or the closed—will characterize the community. Educators have recently gained a large share of this capacity to set the tone of the entire community, for the way the schools and universities develop and allocate the crucially scarce qualities, talent and knowledge. has begun to touch deeply upon all the diverse concerns of mankind. Not only is the educator's performance significant to everyman's future, delimiting his personal and public prospects, but more importantly, how educators function, the nature of the means they use, increasingly determine the actual character, as compared to the proclaimed temper, of the relations between persons.

If a powerful group, one whose activities condition everything else, conducts itself in a humane and liberal manner, those who live within the realm the group conditions will experience their society as a humane and liberal one. Hence with power educators have become responsible not only for exercising their functions effectively, but further for performing them in harmony with the characteristics that people want their community to embody. This larger responsibility arises inescapably from the increased significance of intellect for life, for with power educators are a definitive group in society, that is, a group the spirit of whose activities is the character of our common life. And here we encounter a disturbing proposition: If contemporary education is intrinsically illiberal in the character of its operations, then we are creating a closed, illiberal society, for the spirit of educational practice, which is one of the dominant modes of practice in our lives, defines the actual character of the way of life in "the learning society."

On this matter, students' testimony about their condition is significant. Regardless of the diverse particularities, students in many countries protest educational practices that do not recognize the student's intellectual autonomy; they suggest vehemently that their autonomy is essential to an education that would fittingly harmonize with the freedom that nearly every society professes to respect; and they assert that a community characterized by the established educational practices cannot truthfully claim to be a liberal society. These points deserve attention. They indicate that a society whose character is defined by the character of its educational practices cannot cogently claim to be liberal unless its means of education are liberal. Hence, as happens, innovation has refurbished an ancient issue, that of the liberality of the liberal arts.

Studies Worthy of Free Persons

Many still recall that throughout the Western saga the artes liberales have been studies deemed worthy of free persons; thus the phrase most often denotes the type of schooling its user received. Traditionally, however, the seemingly vague idea of studies worthy of free persons had a precise meaning, which may clarify present difficulties.

The words "worthy of free persons" postulate as a given the autonomy of the student. Even in ancient times pushy parents exaggerated the power of the liberal arts, expecting them to transform slothful children into masterful Caesars. But pedagogical theorists were clear about the matter: No studies mysteriously made persons free; no subject had a liberating potency. The autonomy of the student, his moral freedom and responsibility, was not the consequence but the condition of his education. Only on recognizing the student's inalienable autonomy did the choice of subjects represented by the liberal arts make sense.

What does a youth, aware of her autonomy, want as preparation? She sees life as a continual development throughout which she will always be responsible to herself and others for certain particulars. Owing to these responsibilities, she seeks competence; but having a keen sense of her everchanging possibilities, she cannot say honestly exactly what competencies she will desire as she unfolds her life, and she is loath to let her pursuit of competence hamper her prospective development. Consequently, she seeks an open preparation that will enable her, in the all-important school of life, to move forward independently into whatever matter she feels drawn. Hence neither an introduction to the great books nor the beginning of a specialty, the liberal studies were simply a rigorous discipline in the intellectual tools with which one could gain access to any particular matter. In ancient times this discipline came through grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. But these subjects were not sacrosanct: The liberal arts were thought worthy of free persons because a person who had mastered them could apply herself to any other subject without dependence on teachers.

With the liberal assumption of the student's autonomy, the teacher accepted an important but highly circumscribed function: the self-effacing task of making himself unnecessary. Pre-Rousseauian pedagogy is incomprehensible without realizing that its aim was not to make the teacher more effective, but to make him less important. Formal pedagogy was to help the student arrive as quickly as possible at a point at which he no longer needed instruction. Thus the medieval scholastic, John of Salisbury, asked why some arts are called liberal and gave this unequivocal answer: "Those to whom the system of the Trvium has disclosed the significance of all words, or the rules of the Quadrivium have unveiled the secrets of nature, do not need the help of a teacher in order to understand the meaning of books and to find the solutions of questions."

In sum, the liberal arts presumed that a free person would want to master the tools of learning in order to proceed unhampered by dependence on others in his personal pursuit of competence. The liberal studies in no way caused persons to be free, but were an occasion at which free persons could develop their capacities for independently seeking their personal concerns. The belief that every person is innately free and has the capacity to cultivate his character was the characteristic liberality of the liberal arts. The liberal tradition has been synonymous with trust in the student; in it the educator premised his efforts on a recognition of the student's moral and intellectual freedom. The spiritual independence of the student was so essential that the great teachers of the tradition avoided docilely passive students and taught with acerbic criticisms intended to awaken their listeners' self-awareness. In the liberal tradition, philosophy, a conscious effort at self-formation, begins only when a free person recognizes his mortal limitations and becomes aware of his personal possibilities.

Despite the disappearance of the particular subjects traditionally included in the liberal arts, the liberal premise is still sensible. Recognition of the student's autonomy accords with the pedagogical actualities: No matter how deft one's didactics, their success depends ultimately on the student's consent. An education includes all the attributes a person acquires during his lifetime. In the process of this education, the act of acquisition is essential. No institution gives an education; at most, even the best universities only offer instruction or training, or as the Yale Report of 1828 neatly put it, they help lay the foundation of a superior education. But that superior education had nothing to do with the curriculum of Yale; the superior education was the one acquired in later life through a hard-working person's self-culture. Liberal pedagogy simply assumes that educational responsibility and initiative actually reside in the person becoming educated; after all, the student must live with the ideals and skills he thus acquires. Therefore, students are now asking a proper, significant question. As education has become a definitive function of the community, have educators maintained the liberal assumption as the foundation of their activities? Do teachers assume that the students to whom they offer instruction are free, autonomous agents?

Pedagogical Paternalism

With power educational theorists and practitioners have plunged into pedagogical paternalism. Few now speak of youths acquiring their education. What was once the student's responsibility has become the teacher's responsibility. The school is now blamed if the child fails. Mere opportunities to receive instruction have been converted into "an education," which would exist even if no one responded to the opportunities. "A high school education," "a college education," "graduate education," and many others are offered by various organizations, which seem to have the positive power to educate. Therefore, one "receives" a college education by doing satisfactorily what a college faculty tells one to do, provided, of course, the faculty itself is accredited. Educationists are even looking seriously for techniques effective at "teaching the unteachable." Such usages have shifted nearly the whole burden of responsibility and initiative in formal education off of the student and onto the teacher. This shift has had a grotesque effect on didactics: Learning theory is now conditioning theory.

Contemporary practice has strayed far from the humility of Socrates and Plato. For them, teachers were at most mere midwives who might help a youth give birth to his soul, and who, in giving such aid, taught nothing, simply trying to stimulate, instead, the youth's memory and perceptiveness. Platonic pedagogy entailed the conviction that from the beginning the student was inalienably free and ultimately responsible. "Virtue owns no master: as a man honours or dishonours her, so shall he have more of her or less. The blame is his who chooses...."

In acquiring his education, the student chooses, the blame is his; hence the one thing for which the young are absolutely responsible is their own education. This responsibility is unavoidable because students have the power, whatever the system of didactics, to accept or refuse instruction, to seek out, select, tolerate, or ignore any particular preachment. A boy's duty is to make a man of himself; the responsibility of youth is to educate itself. No agency can perform this task for youths; life puts it up to them, and in it they make or break themselves. Teachers can only challenge—Sapere aude! Dare to discern! Rather than saying that the truth will make persons free, the liberal tradition has perceived that because persons were free they sought the truth.

Exactly when educators rejected this liberal premise is moot. But since mass education developed, the dominant problem for educational theorists has been to ensure that students will learn what teachers try to teach. Thus early in the nineteenth century the influential German pedagogue, J. F. Herbart, denied that education as he defined it was compatible with the doctrine of transcendental freedom, the axiom of the student's autonomy. Herbart believed, as do countless others, that it was impossible to educate if the student was already fully free, for in education the student was molded by the teacher, who should sagely shape the inchoate child into an autonomous adult.

Educating a free agentg seems impossible, however, only to those who have conceptually separated an education from the person who acquires it and have made the education something that is done to the student, not something the student does to herself. Be that as it may, with the denial of the student's autonomy, paternalism flourished. Having defined education as the molding of a plastic pupil, Herbart logically made "the science of education"—the science by which the teacher could ensure that the child would learn what the teacher sought to teach—into the major problem of pedagogy.

Sin of Pride

In developed systems of education throughout the world, the student is now characteristically perceived as a plastic substance that lacks its own will and that is to have a will molded in it by his parents and teachers. Hence educators have stopped seeking studies worthy of free persons and have begun propounding programs that will make persons free. The teacher acts on the pupil's potential for free choice so that, as Herbart said, "it must infallibly and surely" come to fruition. Here is the pedagogue's sin of pride. his arrogant quest for the infallible and sure method. Here the pernicious practice began: Teachers came to ignore the pupil's right and duty to refuse or to seek instruction. Around the world teachers now not only know more, they know better; they know better when the student has profited from his studies, when he should move on to other matters, and whether he should try any particular task. Little wonder that passive pupils fold their arms and say, "Teach me," while the assertive protest in futile despair.

On the higher levels there seem to be pockets of resistance to this pervasive paternalism. One even hears that with the free-wheeling mores of undergraduates, paternalism on campus is no longer possible. But this condition is social, not intellectual; and professors rejoice at the demise of the tradition that the college faculty stood in loco parentis over its students' social doings. The Machiavellian might nevertheless suggest that academic authorities have renounced paternal power in social matters as an unconscious means of protecting their paternal power in intellectual matters, for students who are preoccupied with their social freedoms may easily fail to assert their intellectual freedom. Thus the decline of social paternalism is quite compatible with an increase in intellectual paternalism; and this latter increase, not the former decline, tolls the bell in our schools for the liberal premise and promise.

Intellectually, few think of youths making their own way to maturity through a halting self-education. The Bildungsroman is left to literary critics. The paths to maturity seem charted; the tasks are set, the performances prescribed, the prospective achievements well specified. Examine the system; examine how on every level teachers are responsible for its performance, and how they are carefully prepared in teachers colleges and universities; examine how "objective" tests coldly predict each pupil's probable performance on the next rung of the ladder; examine how diverse diplomas, certificates, and degrees all purport to attest verily that John Doe, student number 1,000,000, satisfactorily completed the appropriate requirements. Examine the system and you will see how paternalism has spread through the developed countries, a paternalism based on the assumption that intellectually the student is patently passive.

"Eppur si muove!" "And yet it moves!" Galileo purportedly muttered while recanting his solar theories. We are hearing similar words from students. The science of education was created by those who saw democracy coming and concluded that they must educate their masters. The ambivalence of this origin has been transmitted to the accomplished work. The science of education has made life more pleasant for the youths it adroitly manipulates. Yet it is the passive pupil molded by the science of education who may prove to be ineducable, for only through alert seeking, the power to pursue or refuse instruction, will a person be able to acquire his character and skills. In the end, the student chooses; she knows, if honest, that the blame is hers. Hence around the world the young insist, Eppure io voglio! But still I will!

To educators willing to face the implications of their experience, this cry tells nothing new. For years both students and teachers have felt trapped. Professors know how often they fail to profess what they tentatively conclude from their ongoing, general inquiries because they feel required to certify that their wards have rotely mastered a particular fragment of acquired knowledge; students equally know how often they are afraid to learn through a game willingness to risk mistakes because they feel driven to learn rotely by the fear that a failed test will ruin their future. We nurture what we call "academic freedom," seeing that given the system it is the best we can achieve; but in moments of silent sincerity we recognize that academic freedom means academic security, conditioned on tolerably good behavior, and that it grants professors little freedom to teach and students even less freedom to learn. These ills are familiar to scholars; and the outrage of students is not significant because it will awaken professors to the spread of pedagogical paternalism. Today's professors were yesterday's students. They too know the score; but until recently both professors and students judged that the system worked too well didactically to risk reforming it radically merely because many felt its manner of operation degrading. This judgment is changing.

As a protest against the malignancy, the demonstrations go beyond an intra-academic appeal to educational leaders. That appeal would have been merited any time during the twentieth century and would not provide an explanation why student discontent has become prominent in many countries in recent years. The appeal is not to educators, but to the public, which only recently became interested in educational matters. The object of the appeal is not only to make a point about the character of current educational practice, but to make people aware of the spirit of communities characterized by these practices, for whereas the risk of reform may be so great that it precludes changing the system solely for pedagogical reasons, the costs to civic ideals of not making reforms may be so much greater that persons will muster the courage to take the pedagogical risks. To foster this courage, the young point to a fundamental contradiction, which is a terrible threat to our future and yet a potential for the creative, cosmopolitan reconciliation of peoples.

In most countries the younger generation has gained from the Cold War two fundamentally common experiences. Whether capitalist or communist, Arab or Jew, black, white, yellow, or red, we have grown up in a rhetorical din in which every mode of communication, the hot and the cool, the electronic image, the printed page, and the spoken word, all reiterated that "our" way of life is humanity's highest embodiment of humanity's highest ideals: dignity and freedom, benevolence and love. Yet whether capitalist or communist, Arab or Jew, black, white, yellow, or red, we have all grown up with an intimate, extended involvement in an educational system that increasingly entails the practical rejection of these great ideals, that increasingly sets the tone of the actual communities in which we live. Students everywhere seek to communicate their awareness, which stems from their immediate experience, of this contradiction between the aspirations of modern life and its characteristic practices within the omnipresent educational institutions.

This contradiction is actual; it is serious; it may even prove to be productive. As an actual contradiction, it will not go away simply as other, secondary aspects of student discontent are dealt with. As a serious contradiction, it will require persons to do something effective to bring their ideals and practices into harmony, for serious damage can be done to our civilization by more intensive student disruptions, by indelicate political interventions, or simply by the disgusted resignations of those with talent, vision, and competence. Finally, the contradiction may be productive if in resolving it persons unexpectedly make creative, humane innovations in civic organizations.

Our educational practices are out of harmony with our professed ideals. This discord gives rise to a tremendous social tension in the postindustrial world. At the same time, fundamental innovations in the arts of communication have thrown our established forms of polity into question. Everywhere schools and universities are under challenge, and their habitual practices are being upset. Such a situation is not only a danger; it is an opportunity as well, an opportunity not for planned development, but for historic innovation, for unexpected, surprising actions taken in the face of difficulty. Neither progress nor regress develops because difficulties are absent; historic change is wrought as persons cast about under pressure for uncertain solutions to perplexing difficulties. The worldwide academic disorders deserve a more imaginative, more dispassionate response than the wail of woe they have primarily engendered, for based on a radical contradiction between the civic ideals that persons universally profess and the pedagogical practices that they everywhere perform, the student disorders may signal the possibility of another period of civic innovation, one analogous to the great era of democratic revolutions.

If educators are to rise to this possibility, their task is not to search frantically for ways to dampen the disorders. To seek historic changes in the midst of tranquillity, free of friction and pressure, is to seek what never was and never will be. Too many commentators cringe at the grave threats to the established system posed by the politics of protest, by student radicalism, black militancy, and right-wing reactions. The tremulous question is too often asked, Can the university survive?

True, threats to the university exist; let us recognize them and marvel at how fortunate we are to have interesting challenges to meet. Life thrives on danger. The spirit grows not as it avoids challenges, but as it surmounts them. Civility thrives not through dead decorum, but with the practice of civility, which in essence is composure under pressure. With a fitting graciousness, let us welcome our dangers, chest out, arms extended, head high, attention alert. In the place of the tremulous question, let us ask the constructive one: How can we make the current difficulties an occasion for dealing constructively with the discontents of postindustrial life?

Towards a Postscript

In writing this essay, I tried to give my basic convictions about what liberal learning can and should do an optimistic cast, recognizing the large secular developments inimical to it. At the end of the decade with "The Dynamics of Decline," my views we considerably more pessimistic about the feasible prospects. The underlying vision of what liberal learning can and should do remained consistent, as it has since then. In both these essays, I voiced my vision from within an idealistic frame of thought, especially in this one, assuming that the commitment to the right principles could mend matters.

I'm starting here to grapple with a problem of diction. I'm drawing all my work together to try to get a prospective readership for it, not to provide those with biographical or historical interests with documents about my work situated as I composed it over the years. In gathering the work together now, I want to I am correcting my long resistance to avoiding gender bias in my diction. The accidents of my biography made me particularly insensitive to gender bias, not from blind chauvinism, but from a sense that an all-inclusive masculine diction best suited an effort to express my ideas in clear, readable prose. My parents established a household after each had initiated independent careers, one in the New York garment industry and the other in finance, in which issues of the women's movement were neither tangible problems nor moving concerns. I grew up rather clueless about gender issues. . . . [I should deal with all this elsewhere along with the other diction problem, working my preferred diction circa 2025 into prose origenally written across the preceding 60 years. The individual >>> the person; real >>> actual; etc. ]

- ↑ 1971: Robbie McClintock is associate professor of history and education, and a research associate in the Institute of Philosophy and Politics of Education at Teachers College. His forthcoming book, Man and His Circumstances: Ortega as Educator, will be published in spring 1971 by Teachers College Press.