Texts:1976 From Problems to Predicaments

- My user page

- Notes to myself

- Draft book proposal to Princeton University Press

- Forms for page setup

- Links to apps go here

From Problems to Predicaments

Reflections on American Social Policy

Draft written while sepcial assistant to the Secretary of HEW, 1976.

American social problems persist, despite long-term efforts to act upon them, despite the expenditure of vast sums to control them. The persistence of social problems suggests that our modes of social action merit critical examination, but the very scale of our social action inhibits that: it is so vast, and touches on so many areas of life, that one has great difficulty defining the controlling paradigm of social policy formation, difficulty criticizing it, difficulty conceiving an alternative. But let us try.

Let us start where most everything is summarized. Twice yearly, the Office of Management and Budget puts out a document designed to help people thread their way through the tangle of social action. This document, the Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance, is a compendious guide to "any activity, service, project or process of a Federal agency... which provides assistance or benefits to the American public."[1] By reflecting on it, we can grasp the mode of reasoning that currently gives rise to social action in its many forms, and doing that we can begin to understand its characteristic weaknesses, to comprehend why action so formulated often leaves the problems persisting.

I

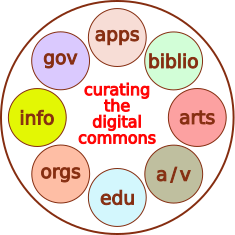

OMB's Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance exists to help would-be beneficiaries find the assistance to which they may be entitled and to facilitate their applying for it. The list of potential beneficiaries is diverse and long—all forms of state and local government, all manner of organizations and institutions, diverse specialized groups and individuals. And the assistance described is not simply a domestic dole; all the 1,086 programs administered by 56 Federal agencies listed for 1978 are based on legislation informed by one or another social purpose, the achievement of which is to be furthered by the careful grant of assistance. "Assistance," in short, is the carrot that makes social policy active in American life.

As far as I can make out, the Catalog does not tell how many dollars, in sum, are disbursable under the programs it covers, but they must be several hundred billion annually, and the Catalog deals not only with dollars, but with "the transfer of money, property, services, or anything of value, the principal purpose of which is to accomplish a public purpose... authorized by Federal statute." The Catalog renders the web of programs relatively comprehensible. The heart of it is a 900 page section, organized agency by agency, describing each assistance program the agency operates. The section, for instance, for the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare is neat, logical, concise, albeit extensive—a mere 276 pages, double column, listing 303 programs under nine divisions. Each program has its number, formal title, in many cases a popular name. The legislative authorization is cited and the objectives of the program stated. Then a wealth of information for potential applicants is provided: acceptable uses and use restrictions, eligibility, application and award procedures, conditions of various sorts, and so on.

All in all, the Catalog works remarkably well and serves as an invaluable map for all those who would mine the variegated lodes of federal assistance. As such a map, the Catalog displays vividly the scope of our social policy and, what is most remarkable, across the whole range, one sees on reflection that a single mode of thinking about social action is embodied in all the programs, despite their diverse areas of concern. The Catalog gives an unusually clear impression of the paradigmatic reasoning by which American social policy has been habitually formed, a mode of reasoning which we shall call the pragmatic paradigm of social policy formation.

Without intending it, the Catalog shows how American social policy makers, working pragmatically, realistically, have been forming policy across the board by following a three-step procedure. The pragmatic view of social policy starts by identifying particular, remediable social problems or needs; it proceeds to devise workable programs designed to ameliorate those particular problems; and it pursues the optimum outcome, the solution of the problem, by relying on the rigorous implementation of the program. Almost everything that passes for social policy, everything in the Catalog, is shaped according to this paradigm of practicality: finite problems, workable programs, rigorous implementation.

One cannot help but be struck, on sampling diverse program descriptions in the Catalog, by how remarkably similar they are, by the way in which all the programs somehow fit into one single format for description. Each of the programs pertains to a definite, limited, putatively solvable problem. The key to getting a program started is getting a finite problem conceptually isolated. This process of conceptual isolation is often manifest in the title of the program, to wit, "13.267 Urban Rat Control," "13.454 Higher Education: Strengthening Developing Institutions," or "12.108 Snagging and Clearing for Flood Control." The problems are significant, doing something about them important, and that goal seems more approachable when it is rigorously resolved into a particular—the control of urban rats is more particular than controlling vermin in general, or reversing urban decay: one can take definite action against rats. Yet, and here we will find the difficulty, everything is interrelated, and in actuality the control of urban rats may not be possible without the reversal of the more amorphous phenomenon of urban decay. Be that as it may, the pragmatic paradigm requires that problems be particularized, isolated, clearly and finitely, so that effective action on the particular can be planned and implemented.

This paradigmatic concern for particular problems defined in ways that will be conducive to practical action, becomes even clearer in the statements of objectives included for each program. Curiously, despite the diversity of concerns covered in the Catalog, the statement of objectives for each program has an identical grammatical format, each begins with an infinitive, the objective of every program is to do certain particular things. Consider a few:

- 10.052: "To attract the cotton production that is needed to meet domestic and foreign demand for fiber; and to protect income for farmers.." 15.403: "To dispose of surplus Federal real property for public park and recreation use and for historic monument use."

- 16.005: "To furnish advisory services and technical assistance to law enforcement agencies and schools desiring to establish drug abuse prevention policy guidelines for school-police cooperation.

- 20.001: "To improve safe operations and uses of water craft."

- 27.004: "To give disadvantaged young people, ages 16 through 21, meaningful summer employment with the Federal Government."

- 30.005: "To assist individuals who have obtained the right to sue in contacting members of the private bar."

Once a problem has been isolated and defined in a way conducive to action on it, the pragmatic paradigm requires that a program of action, dealing specifically with the problem be developed. With Federal domestic assistance, this happens in a two-step process: the government seeks to underwrite programmatic action along defined lines and invites those eligible to implement the program by recourse to assistance. Thus, the Catalog reflects how guidelines for the creation of each program have been created officially through enabling legislation and subsequent regulations, the gist of which is spelled out for each program, particularly in sections on "Uses and Use Restrictions." The significant point here is that this process further narrows the definition of each particular problem as acceptable modes of action on it are operationalized. Through the creation of guidelines, the government in effect states, not only that definite action on a particular problem is socially desirable, but that, in the judgment of those responsible for the creation and administration of the program, action on it should proceed along certain carefully specified lines. These lines are codified by use restrictions and eligibility requirements, which, one must grant, are generally well-conceived, given each program's particular objectives.

In most cases, the federal determination of uses and use restrictions, as well as of eligibility criteria, can be looked at as the first stage of the program design. The second stage really depends on the applicant, who, within the parameters that have been laid down, comes up with a definite plan of action for pursuing the finite objectives of the program, a plan for acting on the isolated problem.

If this plan as judged acceptable through the application and award process, at brings the program to the stage of practical operation, and thus the award process works to ensure that the practical activities made possible by the federal assistance wall be closely linked to the particular problem that has been slated for solution through the program.

When an award as made, an effect the program as set and starts to function practically an the civic arena. This initiates the third stage of the problem-program-implementation paradigm. Although an most programs the government delegates through grants and contracts the actual working responsibility, at takes serious interest an the implementation procedures through required reports and audits, the function of which as to see that its delegates actually work on the problem according to the program that had been agreed upon. There as much room for slippage an this stage of implementation, and when problems persist even after they have been worked on through carefully designed programs, we usually suspect that they do so because the implementation of the program was not tightly enough controlled. That as, we do not question the paradigm of policy formation, but the quality of policy implementation.

Problem, program, implementation: that, an sum, as the paradigm clearly reflected an each of the assistance programs described an the Catalog. The statement of authorization and objectives isolates the problem; the description of uses and use restrictions and eligibility requirements indicates what type of actions by whom the government wall recognize as proper means of working on the problem so defined; the outline of the application and award process specifies how an eligible actor should go about working out with the government a concrete plan of action that wall receive assistance; and the indication of post assistance requirements, as well as of regulations, guidelines and literature, suggest what sort of oversight the implementer can expect from the government. Everything in the Catalog fits this basic paradigm: define a concrete problem, operationalize a workable program of action designed to address the particular problem, ensure that the program is implemented with as much fidelity to the operational purpose and procedures as possible.

One can see from the Catalog how almost every component of American social policy has been shaped by habitual reliance on the pragmatic paradigm of policy formation. The Catalog comes close to being an epitome of American social policy, but it does not quite give a complete outline of this policy, for there is a variant of the paradigm whose fruits do not appear within it. Some aspects of our social policy do not function through the carrot of assistance and benefits, but rather through the stick of regulation. But these regulatory policies, like the assistance policies, are formed according to the pragmatic paradigm: problems amenable to amelioration through regulation are identified, laws or regulations shaped to deal in practice with those problems are worked out, and systems of enforcement are put in motion. Hence in regulatory policy we have a variant of the pragmatic paradigm: instead of problem, program, implementation, we have problem, regulation, enforcement. In both cases, practical action towards meeting definite ends in view is the essence of the matter.

II

Let us question this paradigm. To be sure, such doubt may seem imprudent: social policy without the pragmatic paradigm seems almost unthinkable. Surely enough money is misspent on fruitless effort even with the careful attempt in each instance to specify problems in e productive, solvable way. Surely enough resources ere dispensed without result even with the careful design of programs for accomplishing limited, rigorously specified objectives. Surely too many dollars ere wasted even with rigorous attention to implementation once e program is in operation. The conventional wisdom holds, end would seem to hold rightly, that the pragmatic paradigm is not et fault, but that fault lies, when fault there is, with the human failure to apply the paradigm with sufficient rigor.

As citizens, however, as taxpayers, we ere well aware that we spend a greet deal of money on social services, with yet uncertain results. Greet good has been done, yet the problems persist. With this persistence of the problems, the suspicion grows that our services effect mainly the symptoms of social problems, while the causes of those problems continue to function unabated by e countervailing social policy. Our existing social programs ere facts, actualities; they have en existence independent of the intellectual paradigm that led to their creation. We can question the pragmatic paradigm, not because we object to its fruits, but because we suspect it may have reached the limits of its fruitfulness. Thus, in seeking to understand the persistence of our social problems, we ere free to pursue two courses; on the one hand e practical course of persevering fully in our social programs end commitments end on the other an intellectual course of questioning fundamentally the conceptual basis of present social policy in that hope that from such doubt new possibilities may emerge to complement what now exists.

Already, with phrases about present social policy, we have granted too much to the conventional wisdom, to the reigning paradigm. Americans generally believe that a good deal of government—local, state, and federal—is preoccupied with making and administering social policy, that policy susceptible of improvement verily exists. Let us start by doubting this elementary proposition. In the most significant sense of the word, social policy does not now exist in the United States.

If you will consult your dictionary, you will find that "policy" is really two words, identical in spelling and pronunciation, but fundamentally different in derivation and meaning. One of these words comes from the Greek for proof, and it means a written contract in which one party guarantees to do something for another under certain conditions. When a friendly insurance agent expatiates on the virtues of one or another of his company's policies, he uses this word. The other word derives from the Greek for city, community, citizenship, and it means political wisdom, prudence, artful or wise conduct, and more currently, a governing principle or plan. The diplomat discussing foreign policy provides us with its most familiar use.

Now, one expects that in discussions of social policy this second word is also being used, but on considering the intellectual basis for what we conventionally call social policy, particularly as it is manifest in the Catalog, we will realize that this expectation is radically mistaken. In actuality, social policy, as it exists, has little to do with a governing principle or plan, and much, all-too-much, to do with the labored drafting, implementation, and enforcement of contracts, regulations, and procedures. And in comparison, the turgid intricacy of these would make the ordinary insurance policy seem a model of clarity, even elegance.

To be sure, insurance policies are useful, and so are social policies in the peculiar form in which they have been written out in laws and regulations, in rules, formulas, and codes of operating procedures. And our first course, our active course, should be to perfect and implement these to the maximum of our abilities. But to make sense of all this, to make this incredible intricacy work on the causes of human problems, we need a social policy in the sense of a governing principle or plan. Yet what we lack is social policy in this sense, and we will not develop such a governing principle unless we iconoclastically break through the way of thinking that has led to creating social policies akin to insurance policies.

What is this way of thinking? It is the pursuit of practicality, realism, pragmatic efficiency. It is not that pragmatic efficiency is a bad quality, but that it is an insufficient quality. Although not sufficient, the practical outlook has been dominant in social policy formation: most all of our social programs have come into being in response to exigencies. As a result, the practical end in view invariably reigns supreme, and too few with a modicum of power and responsibility have the time or inclination to search for the proper governing principles.

Is the pragmatic paradigm is a sufficient basis upon for ever arriving at a social policy in the sense of a governing principle or plan? No. The pragmatic paradigm is essential for doing what we are doing, but in trying to discover how to do what we are not now doing, intellectual reliance on the pragmatic paradigm will fundamentally hold us back. The pragmatic paradigm leads to social policies akin to insurance policies—everything is written out in minute detail and for every contingency, every problem, there is a separate policy. The Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance describes a Ptolemaic system with epipolicy spinning around epipolicy, and each year, as our power of social observation increases, the system becomes ever more convoluted—it generates action, but has no governing principle.

To develop a governing principle, to create a sound social policy, we need a Copernican shift. The pragmatic paradigm has the government at the center of social policy in the same way that the Ptolemaic system had the earth at the center of the universe. As shifting the center from the earth to the sun made a new astronomical paradigm possible, so too will a shift of the center from the government to the citizen, the person, make a new policy paradigm possible. Whereas the government defines problems; people experience predicaments. Whereas the government devises programs; people seek to understand their predicaments by theorizing about their condition. Whereas the government acts through implementation; people act through the interplay of leadership and commitment.

In astronomy, the Copernican system, by shifting the earth from the center, seemed to denigrate our planet; but in truth it did nothing of the sort: it put the earth in its proper place and made it, and experience on it, more comprehensible, more predictable, more fit, if less grandiose, as a place to work, live, and love. By shifting the government from the center of our paradigm for social policy formation, we seem likewise to denigrate its function; but in truth we do nothing of the sort: in truth we clarify its proper role; we put it in its proper place from which it can work with more sound, more humane effect.

Let us leave government out of the matter for a while, whether local, state, or federal. Let us instead ask how people experience social problems and how they come to grips and cope with them. In this context, it is an error in a sense to speak of social problems, for people do not really experience discrete and finite problems; people experience predicaments—complicated, perplexing situations from which they find it difficult to disentangle themselves. Most of us most of the time find ourselves in predicaments of one sort or another, but many, all-too-many, find themselves in what can properly be called social predicaments, that is, being situated in frustrating, intolerable social environments, ones so complicated, so perplexing, that they find it impossible to disentangle themselves.

For anyone caught in a social predicament, all the things government defines as social problems are only aspects of the predicament. I could illustrate this with any one of the diverse social predicaments people find themselves in—the union member, a family man, troubled by ethnic fears, alienated from his work but unready to risk a new start, mystified by the distance he feels between himself and his children, deeply uncertain whether their schools serve their needs; or the widow, told she needs a dangerous operation, lonely and isolated, fearful whenever she goes into the street, ignored by her children who are preoccupied and far away, devoid of support and counsel as she wonders, anguished, what to do for her health; or the rural laborer, chronically out of work in a farm economy that has radically changed, acculturated to fear of the city where his only alternative lies, without marketable technical skill, afraid to move but meaningless should he stay.

In all such predicaments, there are examples of many social problems that the government has defined and addressed through particular programs. But to elucidate an alternative to the pragmatic paradigm—let me call it the popular paradigm, for it puts the people at the center—I want to use the archetypal predicament, that of the unwed mother caught in the predicament of living and raising her children in an urban slum. She has the well-known problems —the hassle of welfare, food stamps, a poverty-stricken existence; ineffective, alienating schools for her oldest, no help with the youngest; the gnawing risk of robbery, rape, addiction; an overcrowded, rundown room for an outrageous rent; bleak, fetid surroundings, accumulations of garbage, scurrying rats and roaches, but no better place to go; no past to speak of, no future to hope for, a hard present made harder still by poor health and poor health care. These are but a few of her problems; yet her predicament is more than the sum of these problems.

Her predicament inheres in the complexity and perplexity of it all. She cannot deal with her problems one by one, straightening out welfare today, the school tomorrow, fixing up her room on Friday, chasing rats on Saturday, forming a hope on Sunday, and finding a good doctor on Monday. The predicament is larger than the problems, for everything in her life is interrelated and getting from day to day is a continuous improvisation. If one thing doesn't go wrong, something else will—that is the predicament. For those caught in the most perplexing social predicaments that our national environment offers, life is an unending struggle with the unexpected, the incomprehensible, the irrational, the absurd, in which those who are least prepared for it are condemned to cope with an existence that is the most perplexing.

It may be an error to think that those who are disadvantaged in life are simple, simplistic fold. Rather, it may be the rich and powerful who live the simple lives, buffered by their advantages from the existential impact of the incredible interrelatedness of all things human, at least when things go as they expect. However it is for the rich, those in poverty lead excruciatingly complicated lives in which nothing is certain, nothing is predictable, nothing is to be taken for granted. Look carefully on the road when you next pass a poor man's car. Once such a car might have been identified by make and model, but now it is literally a running wreck, scavenged and pieced together, with doors of different colors, variegated dents, a ruff-idling motor, voraciously consuming oil, but nursed ingeniously into continued functioning, for the moment, at any rate. In such a car, sallying forth must always be an adventure: most anything can happen and ones destination may well not be reached.

This unpredictability inheres in the complexity that is the mundane reality of the disadvantaged. Like the car, which is a car that does not work yet is made, through initiative, ingenuity, and a vast tolerance for uncertainty, absurdity, to work nevertheless, for the moment at least, so too the lives of the impoverished are lives that do not work, but that are made, by grit of making do, to work all the same, for the moment at least. The social predicament of the poor is the predicament of living in a world in which nothing works, and of having to make it work nevertheless. The complexity of such a life can be overwhelming, and the habits of dealing, day in, day out, with such complexities—irrational complexities in which the relation between cause and effect appears chaotic—need to be taken into account by those of us who live in simpler, more predictable environments.

Thus, the habits engendered by living with complexities, habits which the disadvantaged acquire from their existential plight, may explain one of the great conundrums of social policy, namely the apparent passivity, some call it despair, others laziness, of those most in need of help. The conservative clichés that the poor lack initiative, self-reliance, and refuse to do anything for themselves, utterly misperceive the situation: life in the predicament of poverty is a life of forced initiative and self-reliance in a situation so complicated that the results lead nowhere. To live in poverty is to live forever by ones wits, through ones self-reliant initiative in coping with an endless flow of unpredictable situations that come ones way, situations in which even the most minor matters can make or break the day. The appearance of passivity is really perplexity; it is the wondering initiative that one takes when nothing can be done.

That the impoverished live by an imperative initiative, incidentally, may explain the Horatio Algers, not as exceptions to the normal passivity, but as examples of the rule: the poor youth who gets a lucky break proves so much more dynamic than his advantaged peers precisely because the culture of poverty has awakened his power of initiative. For most in the predicament of poverty, however, this lucky break never comes, and they continue to experience poverty, not as a series of problems, but as a predicament from which they cannot escape. The predicament is essentially one in which life is experienced as an overwhelming complexity, in which, try as one may, one cannot disentangle oneself from the vicissitudes of irrational surroundings. Complexity, that is the root condition, the human starting point, and there is a pressing need for a social policy, a governing principle, that can help the disadvantaged create order out of the complexity in which they live and develop meaning in the face of the perplexity they daily experience.

But let us continue to draw out our alternative paradigm. It begins with the recognition of a human predicament, a social situation so complex that the person is unable to disentangle himself or herself. The human response to complexity, the perception of things as a chaos, has always been to theorize. The person caught in a social predicament, and it is not only the poor who find themselves so caught, needs to form a self-correcting theory that will enable him to perceive, understand, and cultivate the latent sources of order in the chaotic realm in which he lives. This need for theory is the second basic component of our alternative paradigm, the popular paradigm. A predicament is a complicated, perplexing situation, and one must first see ones way out of it, and that precisely is the etymological meaning of the word theory. Theory is a seeing through or out of something, a perception of the cosmos hidden in the chaos, and it is with theory that one can begin to disentangle oneself from a predicament.

Theorizing is the first step toward creating simplicities, toward disentangling oneself from complexity and perplexity, the first step that anyone caught in a social predicament must take in order to get out. The pragmatic realist will scoff at this praise of theory, seeing it to be impractical as a means of solving the particular problems that beset those in predicaments, but that would-be realist should look at the way social change, real, substantive social change, in fact occurs.

Let us stick with the hard case and ask which are the dynamic segments among the poor and disadvantaged? They are precisely those who have formed a theory, a theory about their condition and their potential for the future. These theories rest on various concepts: racial pride, ethnic solidarity, class consciousness, personal self-help. These theories in substance run the gamut of possibility, from maximum feasible assimilation to complete separatism, from the assertion of a puritanical ethic to the self-conscious cultivation of crime. Perhaps the most sophisticated of the theories are those least easily perceived in the cacophony of public opinions, those applied in quiet efforts at community organization. Here, anthropology, sociology, history, psychology, art, literature, and religion, are drawn on by those who would give themselves and the members of their community a more productive sense of past and future. But, be the theory sophisticated or unsophisticated, sound or unsound, the content of the theory is not at first essential. What is first truly important, what is paradigmatic in the phenomenon, is the presence of theorizing itself, and the relation of that theorizing to the social predicament. To diagnose ones plight, to assert ones right, to define and demand equality, to exercise ones liberty, to plan a future: all this is to use theory to convert a predicament into a purpose, for theorizing culminates in commitment.

Such theorizing, such an effort to see through the social predicament, to understand the complexity, is crucial for anyone caught in a social predicament, for with it comes the occasion for commitment and leadership, for human, not governmental, action. This, I believe, is the third stage of the popular paradigm. The impoverished, without theory, caught without hope in their social predicament, are uncommitted, easy to manipulate but very difficult to lead. As people among them begin to theorize, they become committed and start to lead, spreading their theories and eliciting, through that, commitment in others.

People acting from commitment will encounter obstacles; in the face of these, they will change the situation or adapt their theory to take the obstacles into account. People acting from commitment will find themselves in conflict, meaningful, serious conflict with those committed to other theories. Sometimes the conflict becomes tragic, as with Malcolm X, whose saga well exemplifies the paradigm of predicament, theory, commitment. But overall, the conflicts and disagreements are constructive, leading through the dialectic of life to sounder theories and more effective commitments. For the most part, people acting from commitment will find themselves, as they transcend their conflicts, drawn into intelligent cooperation with others. Thus, their actions gain a strength greater than that they alone possess.

In such ways, theory, as well as action based upon it, becomes self-perfecting and ever more inclusive in its scope of operation. As committed groups work out their differences, reinforce their efforts, a governing principle spontaneously emerges, informing diverse actions in diverse situations with a shared, popular purpose. In the same way that a predicament is more than a congeries of problems, so too is committed action based on theory more than the implementation of a range of programs. Committed action is integral action, action that takes into account the interrelatedness of all things, and ever further, action that makes constructive use of the interrelatedness. The implementation of programs may solve problems, but the interplay of committed actions based on theories enables people to lead themselves out of their predicaments.

According to the popular paradigm, a real social policy, a governing principle, comes into being as people perceive their social predicaments, form theories about these, and on the basis of such theories make commitments, which, if the theory is at least partially sound, sill start a development, through constructive conflict and cooperation, by which people sill lead themselves out of their predicament. Yes, this paradigm is popular in the fundamental sense, for it puts faith in the people and their politics, in the interplay of real social conflict and cooperation, which leads, when guided by the cultural capacity of all people to perceive the better relative to the worse, to the emergence of governing principles. Only with such a popular paradigm, operating in the actual polity of people living among people, can real governing principles develop, principles that sill enable the people to lead themselves out of their predicaments.

So far, se have left government out of the popular paradigm. In reality it is an integral aspect of the paradigm, not as something else that, from its independent place, sill operate on the cycle of predicament, theory, and commitment, but as one among the many things inevitably present in the predicament, in the theory, and in the commitment. Those who serve others through government, should try to take full and subtle account of their presence in the popular paradigm.

Criticism does not destroy, but incorporates and transcends. The popular paradigm should not destroy the pragmatic, as if it somehow could, but should incorporate and transcend it. Internally, the government sill continue to function primarily by the pragmatic paradigm. But the pragmatic should, if it would contribute optimally to social policy, be incorporated into the popular paradigm, which is a profoundly political paradigm, and this incorporation brings with it certain further standards that the government on all its levels should seek to meet in the design and provision of social programs.

Let us illustrate this presence of the government in the popular paradigm first on the local level, on the level on which social services are delivered. The paradigm begins, not with the social services, but with human predicaments. In those predicaments, social services are a crucial resource, one which must be provided. But those providing social services should do their utmost to take real predicaments into account in their provisions. And each predicament is not merely the particular problem addressed by a service, but the experience of complexity, unpredictability, irrational incomprehensibility. Consequently, whatever social services do programmatically for the client, they should do without aggravating the pre-dicament, without adding to the complexity, unpredictability, and irrational incomprehensibility that the client experiences.

To ameliorate human predicaments, social services should be delivered in a way that helps the client create simplicity, predictability, and comprehension in his or her surroundings. To do this, those working in social services need empathetically to enter into the social predicaments of their clients, to anticipate the theoretical resources that their clients may have, to make intelligent, defensible, critical judgments about these theoretical resources, and then to act in concert with the most constructive of them. This is a most difficult task, requiring great sensitivity, penetration, and involvement. This is the task in which government takes responsibility not only to function mechanistically with respect to particulars, but further, morally, as one among the many educators of the public. Unfortunately, this is too often not the case and thus the outcry across the range of social action, from businesses, universities, and cities; from the poor, the sick, the abused—however much help deals with the problem, it all-too-often complicates the predicament. As anyone who has seen Weisman's wrenching film on Welfare is aware, the delivery of social services can have effects that are certainly not educative.

That social services can be experienced by clients as a most troubling part of the predicament itself, as one of the most perplexing complexities in the chaos that is their plight, presents government with a very subtle difficulty. To get out of a predicament, people need desperately to theorize, to project order, simplicity, control, onto their surroundings, whereas the government on every level will insist first on order, simplicity, and control in its systems. Here develops a clash of cultures. What creates order and control in the governmental system frequently aggravates the predicament of the clients, making the world they experience seem to them more complex, more irrational, more uncontrollable. As things are, too frequently the burden of adaptation lies, not with the government, but with the client, and the tragedy of this is that the client, especially the poor client, the one most in need of help, will make do in this situation, for it conforms to the fundamental perception that life is a predicament. Thus, although Welfare will often outrage middle-class audiences, for the human plight it depicts offends their expectation of order, those on welfare, caught in the real predicament, may vent their anger momentarily on being sent from office to office, form to form, worker to worker, but they won't do much about it because basically they do not expect that their experience should be otherwise, that their predicament should be simple, rational, and controllable.

This capacity to put up with complexity that one possesses when in a predicament places a heavy burden on those who deliver social services, a burden to adapt services to the predicament of their clients, even though the clients are able, and in the pinch willing, to adapt to the system, no matter how irrational it may appear in their field of experience. In order to do this, the providers of social services need sophisticated and sensitive theories that will enable them to perceive, understand, and cultivate the latent sense of order the client perceives in the predicament. These theories need to reflect the Copernican shift by having the client, not the governmental service, as the main concern. Solving the problem is not enough; the problem should be solved in a way that cultivates the client's capacity to understand and lead himself out of his predicament.

Thus the government, seen as an aspect of the human predicament, is also brought to the second stage of the popular paradigm: equally as much as those in predicaments, people seeking to help need to theorize about the predicaments. This theorizing will have to go far beyond the well-established effort to rationalize the techniques by which services are delivered; it will have to try to understand in its full, integral complexity the predicament of the client, to give comprehending help in a way that provokes comprehension in the recipient.

And effective theorizing within the service agencies will lead to real commitments by them. They, like other theorizing groups, will become advocates of a way. This willingness to advocate, I suspect, is a key to humanizing bureaucracy. People in every social strata fear that they are being manipulated by their government, and people in government, most of whom sincerely have no intention to manipulate, become more defensive, pull back, and do everything whenever possible strictly by the rule. Yet, paradoxically, to keep from manipulating, those in government often may need to seek openly to lead.

Bureaucratic ends become dominant where no human ends have been established. It is safe and secure for the service agencies to keep a low profile, to provide an impersonal, programmatic assistance, to disperse welfare checks, health services, classroom instruction, as impersonally as possible, according to the rules of procedure. It is demanding and risky to inform those rules of procedure with theories about the social predicament or with humane, fallible commitments to principles and persons. Yet such theories and such commitments are the way to achieve a responsible responsiveness in bureaucracies.

Predicament, theory, commitment: these are the stages of the popular paradigm. This paradigm describes how social policy ultimately emanates from the person, the person living in a social predicament, and the person in government helping others deal with the predicament. This paradigm makes social policy depend on politics, on the public interaction of people and groups. Within this paradigm, there is room for the pragmatic paradigm, for the government still to define problems and to implement programs; even more, the popular paradigm shows that there is a pressing need for the government to do precisely that. But in showing this need, it shows also that it does not suffice for the government to work by the pragmatic paradigm alone. The government needs to shape its work based on the pragmatic paradigm to accord with the popular paradigm. Whereas the pragmatic paradigm is an administrative paradigm, the popular paradigm is political, and the end result of the Copernican shift here called for will be, should it take hold in actuality, to remove social policy from isolation primarily within the realm of administration, and to put it back in the midst of politics.

III

Is there not already far too much politics in social policy, as with the infamous busing issue, for instance? I mean politics in a rather different sense. What has passed for politics with respect to what has passed for social policy has centered on questions of what the government should and should not do. Such a politics is a governmental politics, one built on the unquestioned assumption that government is the central force in social policy. Such politics is also a residual politics that persists when almost all believe that social policy must be framed by the pragmatic paradigm, becoming thus ultimately an administrative matter. When social policy is seen as a matter of administration, the politics that appears pertinent to it is the politics of interested groups, all reaching for the fruits of the administrative apparatus. Hence, as the pragmatic paradigm came to dominate in domestic affairs, so too did the group theory of politics.

Interest group politics determines who gets what when, but the politics of interesting groups works out who stands for what why. The politics that is important to the popular paradigm is not the governmental politics that discloses what the government should and should not do, but the popular politics that discloses where the people really do and do not stand, not vis-à-vis the government, but vis-à-vis themselves. Take busing, for instance: the real issue there for popular politics is not whether the government should or should not bus, but where ghetto blacks and Catholic ethnics really stand vis-à-vis each other. The aim of politics understood by the popular paradigm would be to get the leaders of both groups to look at the predicaments together, to negotiate points of common understanding, points of hopeless irreconcilability, to create a structure of common expectations, expectations that each group could have of the other. By partaking as an interested, involved party in such a popular politics, the government might not only help solve certain problems, but help people lead themselves out of their real predicaments.

Social policy on every level has been excessively isolated from politics, from hard, serious, committed public discussion. This absence of politics, this lack of commit-ment and leadership, this failure to theorize, stems ultimately from the predominance of the pragmatic paradigm. To be sure, the pragmatic paradigm makes government central in what passes for social policy, but in doing that it cur-iously removes social predicaments from the realm of politics in its best sense, in the sense of public leadership. It does this by converting social policy into a mere function of government, whereupon the matter ceases to be an element of governing.

American government became involved in social action, not so much through a political choice, but out of practical necessity. When forced to act by situations such as the Great Depression, the government generally used the pragmatic paradigm to key its actions to the apparent necessities, quite rigorously refraining from the assertion of principles within the political arena. In effect, in situations of exigency, in the face of political predicaments, our politicians have been afraid of politics in the popular sense, and the pragmatic paradigm has been used to take social questions out of politics by sublimating them into government, ultimately making them tasks of administration. Thus, with respect to social problems, everyone has been told they can expect something from government. But we have not used our politics through open, rigorous, committed discussion to tell each other as citizens what we can expect of each other as matters of principle with respect to our multiple social predicaments.

For all our programmatic legislation and our landmark adjudication, we have really established nothing as matters of principle between citizens, as matters of fundamental agreement and mutual expectation that will stand regardless of the interplay of self-interest. There is one possible exception to this indictment: with the social security system, we may have established, as a matter of principle that we share as citizens, the proposition that no one should be compelled to an old-age of utter destitution. Yet even with our program of insurance against the loss of earnings in old-age, which came into being as part of a pragmatic response to an emergency, a program that still does not cover all, there are distinct signs, as the program begins to falter from technical flaws and demographic developments, that the political will behind it may be far weaker than it seems.

Outside of that potential exception, however, we have really established nothing as a matter of principle. We came closest to it with the simple, fundamental principle that we will respect each other regardless of race. In the early sixties, through committed interplay over civil rights in the public arena, social policy in the sense of a governing principle was developing. Then people were perceiving their predicament, forming theories about that predicament, making commitments on the basis of those theories, acting in and on the public, taking stands, engendering opposition, persuading, converting, steadily establishing a principle. But then as a difficult war became more burdensome and social tension seemed a growing danger to political stability, political leaders decided it was time to act according to the pragmatic paradigm, and high-minded legislation passed, which had the effect of relegating a matter of principle to government to deal with through regulation.

Now I do not hold that this regulation has been of no benefit to those caught in the predicament of discrimination, but I do hold that the cost of these benefits has been very high—they have come at the cost of not establishing the principle. Respect for each other regardless of race was transformed from a matter of conviction to one of compliance, and because it was never really established between us as people as a matter of conviction, so many complaints about failures of compliance are building up in the regulatory system that that system may soon fail further to function—that is the ultimate impracticality of the pragmatic paradigm: programs can stand adversity only insofar as they stand on principle.

By itself the pragmatic paradigm is impractical: it cannot be used as an alternative to a popular politics. Workable, effective social programs and systems of regulation cannot be based merely on a legislative will, or a judicial will, or an administrative will, for these wills are transitory. Workable, effective programs and regulations have to have behind them a solid political will, an inclusive popular will, one that will persevere despite adversity. There are serious technical imperfections in many of the social programs that we have formed by the pragmatic paradigm, but the really serious inadequacy of these programs is not in the technical imperfections, which can be corrected by further use of the pragmatic paradigm. The serious inadequacy is in the political will behind the programs. To develop this popular will, to discover what each of us as citizens can expect from each other as matters of principle, we need to go beyond the pragmatic paradigm, seeing social policy, not as a function of government, but as a solemn popular commitment.

Habits of relying on the pragmatic paradigm and seeing social policy as a function of government, however, are deeply ingrained. In our system, the functions of government are carefully divided, and in the realm of social policy each branch has habitually confined itself quite rigorously to its proper governmental function. This is as it should be. But to perform a function of government is not the same as exercising the responsibility to govern. The responsibility to govern is indivisible, and all people, those within and without the government, share equally in the duty of its exercise. Timidity in this duty has been our habitual trait. The attraction of the pragmatic paradigm to a timid executive, a timid legislature, a timid judiciary, as well as a timid populace, has been that it enabled social policy to be neatly integrated into the functions of government, integrated in a way that seemed to free everyone from the difficult, demanding, and dangerous task of governing with respect to social predicaments.

By relying on the pragmatic paradigm alone, the people and the branches of their government could timidly deal with perplexing social predicaments simply by doing their jobs, and that has been the characteristic feature of social action in America—at best, everyone involved has been simply doing their jobs. Relying on the pragmatic paradigm, the people could look to the government, not to one another, whenever social problems became palpable, whereupon a majority let it be known that the government might act. The legislature could simply wait until the demand for a social program became clear, whereupon it could create a practical program, with a generous authorization and a more prudent appropriation. The judiciary, as has been its traditional wont, could simply wait until the telling case came up, whereupon it had to interpret judiciously the law of the land. The executive could simply wait, giving a nudge or two, until the other two had acted, whereupon it could implement the mandates it thus received. Leadership came from events. The predicaments needed never be faced. Theories needed never by formed. Commitments needed never be risked. The people needed never be moved. The comfortable could persist in their comfort, the prejudiced in their prejudice, the perplexed in their perplexity. Thus we came to have a system of social legislation and services with no basic commitment to the principles on which it could stand.

Our social problems are likely to continue persisting so long as this most paradoxical, political predicament persists, so long as we as a people, whose polity rests on the popular paradigm, grow increasingly afraid to face our predicaments, to theorize about them, to commit ourselves in action, so long as our fear of politics deepens. We must do more than solve problems through rational administration—that is our predicament.

- ↑ The CFDA no longer exists, replaced n 2018 by SAM.Gov. See "Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance (CFDA): What It Was" by Troy Segal, Investopedia